Introduction

Greetings fellow developers and tech enthusiasts,

Around 2 months ago I started developing XSKNet, a custom network stack for Linux. The project is still in its early stages, but I thought it would be a good idea to share my experience so far.

The architecture of XSKNet is built around the use of AF_XDP (XSK) for kernel bypass. This technique allows for more efficient data handling and faster communication, bypassing the overhead of the traditional kernel stack. The project is structured around a daemon and user clients, each with its own specific functions and usage.

The daemon is responsible for the creation and management of the XSK sockets, as well as the handling of the incoming and outgoing packets. The user clients are responsible for the communication with the daemon, and the creation of the XSK sockets. The daemon and clients communicate through a UNIX socket. Packets are sent and received through the XSK sockets.

XDP

XDP (eXpress Data Path) is a Linux kernel technology that provides a high performance, programmable network data path. XDP is a general purpose packet processing engine that can be used for a variety of purposes, such as packet filtering, policing, load balancing, etc. XDP programs are usually written in C and compiled to BPF bytecode, which is then loaded into the kernel. XDP programs are executed at the earliest possible point in the packet processing pipeline, before any other kernel processing takes place. This allows for the most efficient packet processing possible.

XDP programs can be loaded in using multiple modes. The valid values are ‘native’, which is the default in-driver XDP mode, ‘skb’, which causes the so-called skb mode (also known as generic XDP) to be used, ‘hw’ which causes the program to be offloaded to the hardware, or ‘unspecified’ which leaves it up to the kernel to pick a mode (which it will do by picking native mode if the driver supports it, or generic mode otherwise).

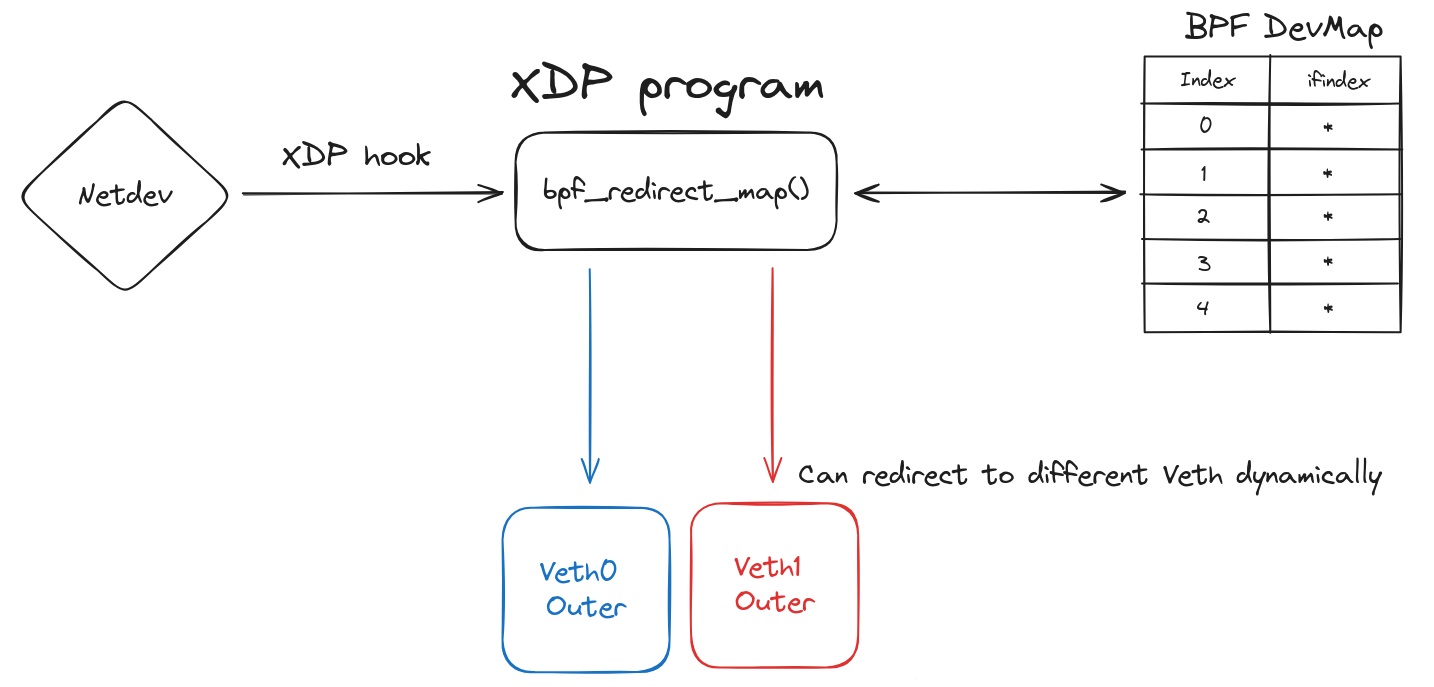

Daemon manages the BPF map here we use BPF_MAP_TYPE_DEVMAP to redirect packets to different network interfaces including virtual interfaces. The map is a key-value store that can be accessed by both the kernel and userspace. The kernel can access the map through the use of BPF helper functions. The maps can be pinned to the filesystem, which allows for the map to be shared between multiple programs. The map is created by the daemon and pinned to the filesystem. The clients can then access the map by loading the map from the filesystem.

AF_XDP

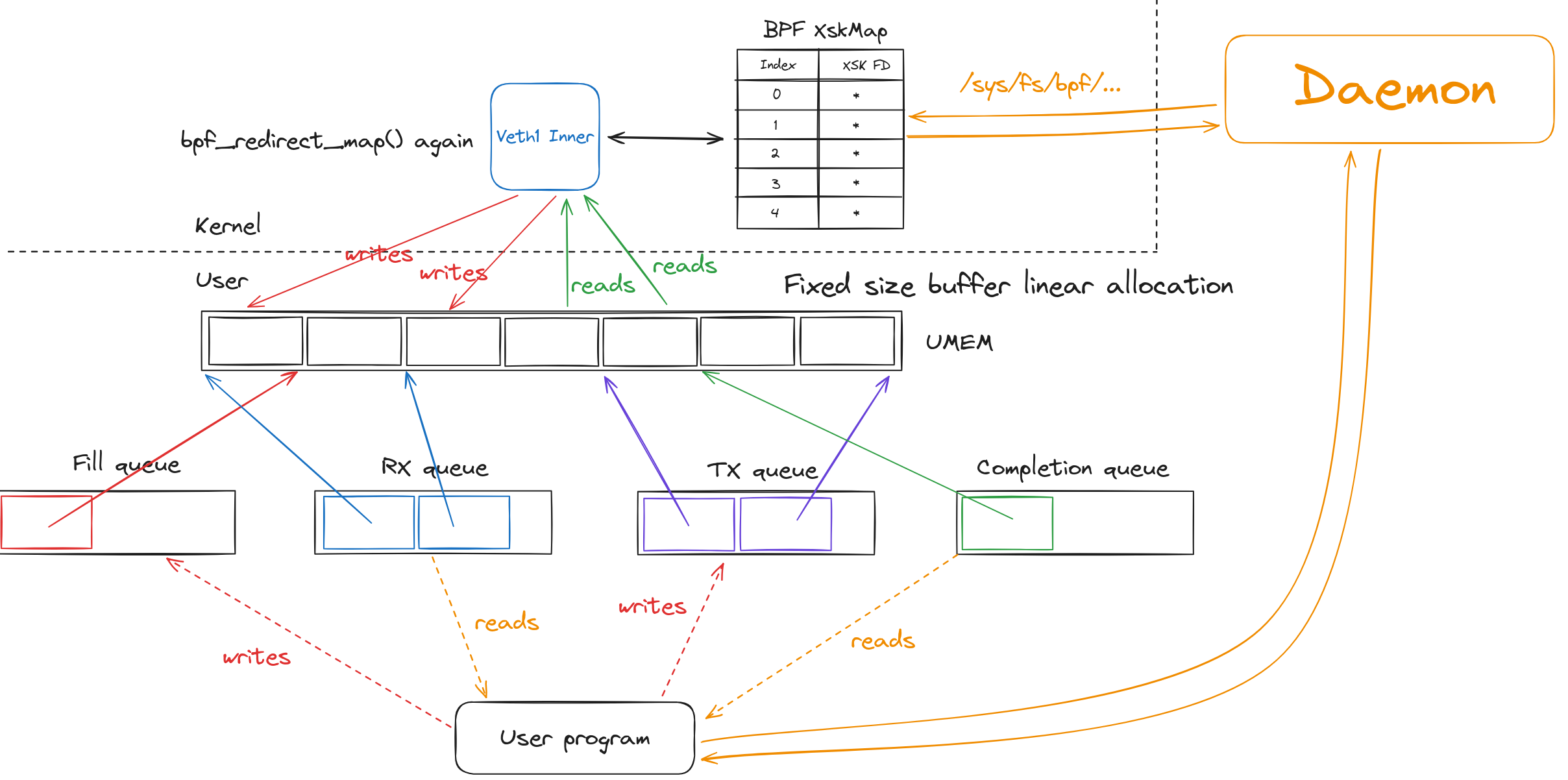

The kernel and userspace share a common memory region called UMEM, which is used to exchange packets. The kernel writes packets into the memory region, and the userspace reads them and vice versa. This is done through the use of memory rings, which are circular buffers that contain pointers to the packets in the memory region.

The UMEM is split into contiguous equally sized chunks called frames that are referenced by descriptors which are just offsets from the start of the UMEM. The interactions and synchronization is done using the aforementioned rings. Most of the work is about managing the ownership of the descriptors. Which descriptors the kernel owns and which descriptors the userspace owns.

Available rings are:

- COMPLETION: Kernel writes to this ring to notify userspace about the frame descriptors that has been successfully transmitted.

- FILL: Userspace writes to this ring to notify kernel that these frame descriptors can be used to write packets into.

- RX: Kernel writes frame descriptors of newly received packets to this ring.

- TX: Userspace writes frame descriptors of packets that it wants to transmit to this ring.

Each UMEM is associated with a FILL and COMPLETION queue upon creation.

RX and TX rings are associated with the XSK socket. This socket is bound to a specific network device queue id. The userspace can then poll() on the socket to know when new descriptors are ready to be consumed from the RX queue and to let the kernel deal with the descriptors that were set on the TX queue by the application.

Now the only thing left to use the XSK socket is to load the XDP program into the interface we want to receive packets from and insert our XSK socket file descriptor into the map.

When the kernel receives a packet (more specifically the device driver), it will write the packet bytes to a UMEM frame (from a descriptor that the userspace put in the FILL queue) and then insert the frame descriptor in the RX queue for the userspace to consume. The userspace can then read the packet bytes from the received descriptor, take a decision, and potentially send it back to the kernel for transmission by inserting the descriptor in the TX queue. The kernel can then transmit the content of the frame and put the descriptor from the TX to the COMPLETION queue. The userspace can then “recycle” this descriptor in the FILL or TX queue.

A free list is used to keep track of the available descriptors. Since buffers are allocated in a contiguous memory region and are of the same size, the free list is just a list of indices into the memory region. The free list is used to keep track of which frames are available for use. When a frame is used, it is removed from the free list. When a frame is no longer needed, it is added back to the free list.

When you bind to a socket, the kernel will first try to use zero-copy copy. If zero-copy is not supported, it will fall back on using copy mode, i.e. copying all packets out to user space. But if you would like to force a certain mode, you can use the following flags. If you pass the XDP_COPY flag to the bind call, the kernel will force the socket into copy mode. If it cannot use copy mode, the bind call will fail with an error. Conversely, the XDP_ZEROCOPY flag will force the socket into zero-copy mode or fail.

Rest is still in progress, I will update this post as soon as I have something to share. I’m currently trying to route packets that are transmitted from the userspace to the kernel and then to the network interface.